Coaxing Lightness from a Stubborn Material

The transformation process in cities, the mobility turnaround, and the importance of nature and public space in urban development.

There’s a lot of dynamism in horticulture and landscape architecture that can open up new options.

A conversation with Uwe Schneidewind, economist and mayor of Wuppertal

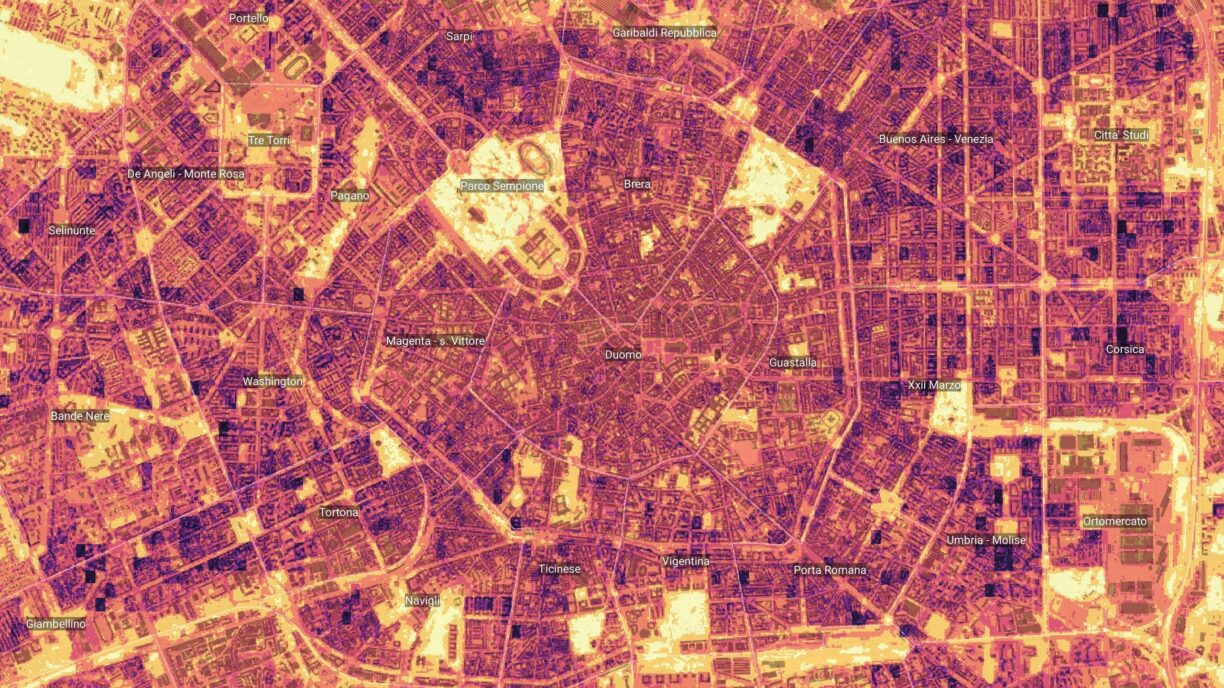

The scientific community uses the term “the great transformation” to describe the epochal changes of the 21st century in the light of sustainable development. By 2050, about eighty percent of people will live in cities. Urban turnaround thus becomes a node within the larger framework of a successful future policy. This is also the subject of the book Die Große Transformation. Eine Einführung in die Kunst gesellschaftlichen Wandels (The Great Transformation. An Introduction to the Art of Social Change) by the economist Uwe Schneidewind, which arose from his work as President of the Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy until 2020. The author, who was born in 1966, is, among other things, a member of the Club of Rome and for many years was also an influential voice on the German Advisory Council on Global Change (WBGU). He was elected mayor of Wuppertal in 2020 as a political newcomer (Alliance 90/the Greens, known in Germany as “Bündnis 90/ Die Grünen”). Based on a WBGU report on “The Transformative Power of Cities”, our conversation with economist and politician Uwe Schneidewind addresses important urban development issues, particularly in Europe.

Uwe Schneidewind © Photo Medienzentrum, Stadt Wuppertal

The transformative power of cities: what role can Nature play there?

Schneidewind: “An increasingly important role. Park design has always been a major impetus for urban development. In Wuppertal, for example, we have the Bürgerparks (literally “people’s parks”), which were created at the beginning of the 19th century. This made it clear that actual recreational space is an important factor in quality of life, but also a factor in wellness, in regeneration. Thus, city green space has always played an important role in urban development. Climate change makes it clear that the design of the natural environment in cities makes a crucial contribution to urban quality of life. When it comes to issues like attractive surroundings, the look and feel of cities, we’re seeing a shift in values, and of course that gives natural design in cities a whole new role.”

What steps are needed to properly play this role? Technological? Cultural?

Schneidewind: “Culturally, the topic has caught on, this awareness that we need more green, and to some extent more blue, more water in the city. The challenges are now more economic in nature. Where do you create these open spaces, where do you find the land? How do you balance this with a general trend toward higher density in cities? We need more living space, not more urban sprawl. So in many areas modern urban development plans are focusing on more density, and this also conflicts with making space for urban greenery. That’s where new technological options come into play. Vertical greening issues, how to bring greenery onto and inside buildings. There’s a lot of dynamism in horticulture and landscape architecture that can open up new options. This also applies to the movement toward water. For a long time, water was considered a supply and disposal channel, and now it’s becoming an attractive urban space. These processes of opening up to water, redesignating former port and storage facilities, industrial sites, can be seen in many cities. So there are a lot of economic challenges, because invariably there are conflicting uses. And to some extent there are also conflicting uses in terms of institutional policies, planning regulations, that are important to resolve in a positive way, so that processes of opening up then also become possible.”

So creating, generating more open space is a challenge even for a mayor?

Schneidewind: “It sure is. Especially for a mayor of a municipality with a lot of debt like Wuppertal. Of course, public space competes with private use, especially in attractive locations and areas. Of course, it’s easier if you can also publicly secure those areas and develop them accordingly. We’re trying this with the Bundesgartenschau 2031 (the German national garden show) using hybrid formats. That means that we develop areas jointly with private investors, so that one area can then be used privately for residential development, for example, but the other area remains public, so investment possibilities can actually be expanded quite a bit.”

Major initiatives are often rejected in referendums. How did you manage to win over the citizens of Wuppertal for the Bundesgartenschau?

Schneidewind: “It was close. We won it by just under 52 percent. It’s still extraordinary, because these major projects usually result in a groundswell of rejection and negative energy. Because often the rejection isn’t just projects-pecific, but is rather an expression of mistrust and frustration with the government. These kinds of referendums rally all the forces of naysayers in a city. And then active supporters really have to mobilize.

We have to distinguish very different forms of participation. One is simply asking for opinions. And opinions today are highly tinged with emotions. People with absolutely no involvement in urban communities then express their individual dissatisfaction through such votes. Much more important for participation, and for urban design, are all the people who very actively participate through codesign and joint production of the city. This sort of participation is what moves cities forward. And there’s more and more of it. The people we call urban gardeners, people who get involved in their own neighborhoods, in urban gardening, in watering the trees outside their homes, who show very concrete and even social commitment to their neighborhoods, that’s actually the primary form of participation, which then develops power in the cities.”

Cities develop into regions. What does this process mean, what does it entail?

Schneidewind: “It actually creates great opportunities. When you think regionally, you can bring together the various functions of living, working, relaxing, and smart mobility planning in a completely different way. At the same time, we see how the logic of municipal finances is structured, and how difficult it is to engage in truly strategic regional cooperation across municipal borders. It’s a dilemma. Right now, municipalities often still pursue the same investors so that as much business tax as possible can be generated in their urban area. There’s competition for certain infrastructure in their own cities, whether it’s hospitals or theaters. Thinking in terms of a large urban area would create more potential opportunities. At the same time, in our experience the sense of identity is still often tied to an individual city and only peripherally to the region as a whole. We’re working on this, but it’s a much slower process than we’d like.”

Thinking in terms of large urban areas – doesn’t that conflict with the idea of the 15-minute city?

Schneidewind: “I think the 15-minute idea is more of a guidepost for a much more integrative way of considering urban development. Using Wuppertal as an example, in 15 minutes you can get to surrounding green areas by e-bike from almost any part of Wuppertal. So in my view, both are possible, especially in very dense, networked urban areas. Depending on where you actually are in this space, very unique and individual 15-minute architectures emerge. For people who’d rather live in the country, but want to combine that smartly with work and healthcare. People who want to live in the heart of the city but still need open spaces. Someone whose needs won’t be fully met within a small radius of two by two square kilometers. But the basic idea of the 15-minute city carries over very well to these kinds of networked, densely urban spaces. I’m very optimistic about this, especially here in the RhineRuhr region. By train from WuppertalVohwinkel, in 15 minutes you can practically get to Düsseldorf.”

So mobility plays an important role in large urban areas that also have rural sections. How can sustainability develop here?

Schneidewind: “Mobility is increasingly measured in terms of accessibility. The question of how we create accessibility will probably shift bit by bit from individually owned automobiles to other mobility links, especially in large urban areas. In other words, where rural areas are interspersed, cars will have a role to play. But not in the sense that you drive from point A to point B, if B is somewhere in the center of a large city. Instead, there will be links to the next park and ride, where people will use other mobility options. This will be within a much more networked structure. It won’t start in rural areas, but will develop outward from urban centers. In large cities and the centers of large cities, automobiles will play an increasingly minor role, because other qualities of city living will be important there.

This has been implemented for some time in a number of cities in Scandinavia and the Netherlands – in Amsterdam, for example, where you can’t drive into the city center anymore. The more consistently this is implemented, the more the idea of parking in front of a store, a department store, and then simply loading up goods will disappear. Even if you come by car, you get to experience the qualities of the big city by parking the car outside, either directly on the outskirts of the city or at the park-and-ride 5 km away. Then you take the train into the city center. This change in direct urban mobility will create a big shift in mobility patterns in rural areas too.”

Looking at the future, does private ownership of land conflict with the sustainable development of urban areas?

Schneidewind: “We’ve noticed that when cities ensure longterm public ownership of a large part of their land and buildings, like in Vienna, they gain an advantage over cities whose overall housing policy has resulted in more massive privatization, including in terms of mobility policy and sustainable urban design. You can reinforce public welfare features through public ownership of land and buildings. It’s a lot harder to deal with private ownership when access is no longer possible. Hybrid solutions could play a significant role here. These solutions could be based on public ownership, but include leasehold rights for private investors so they can use their capital to design things jointly with the public sector and thus bring public and private interests together in a positive way. The starting point, of course, is that the public sector has to have at least some kind of leverage. Cities that were smart enough to keep a significant amount of land in their own hands during the era of massive privatization are truly blessed.”

If it’s in the common interest, should there be an enforceable expropriation policy?

Schneidewind: “Certain instruments, like the right of first refusal, are already available to municipalities today. Now windows of opportunity have also appeared with newly reconfigured downtowns. Changes in shopping behavior have caused the value of Kaufhof chain stores and many other properties to drop drastically, and they’re being vacated because large retail subcontractors are leaving the city centers. This creates windows of opportunity for public acquisition of these buildings, making it possible to implement a completely different approach to inner city design.”

Shouldn’t we also consider some fundamental corrections to our economic system?

Schneidewind: “Going one step further to put certain forms of private property in the city into public hands, in other words to effectively nationalize them, will be a subject of hot debate for years to come. We had this in Berlin with the referendum on expropriating large real estate companies. At the very least, we saw an increased acceptance of the fundamental legitimacy of considering something like this and bringing it into the political discussion. There’s a sense that we actually need this discussion. Yet it will be incredibly difficult to gain majority acceptance for this. If even the approach to tax breaks for the wealthy is sacrosanct, I wouldn’t want to imagine the debate if politicians were to demand widespread nationalization of our urban areas in order to make cities more sustainable for the common good. There’s no grassroots support for that. What I would like to see is a much more open discussion in the scientific community. Mainstream economic sciences actually engage in no critical discussion of many of these side effects. As a result, the intellectual sphere that would be required to create political programs and demands doesn’t exist. We still have a long way to go.”

Does the economist in you sometimes argue with the politician in you?

Schneidewind: “They actually get along pretty well. They’re also both frustrated by how little can be negotiated in emotional worlds charged with populism. Even regarding things that can actually be discussed in a reasonable manner. The politician in me wishes that what I the economist and many others have thought about in terms of perspectives and analyses could enter the political discourse in some way. Often it doesn’t, because we’re well aware that as soon as certain types of arguments are brought into the political arena, populism immediately blows them away. It can be sobering. I suspect this is an expression of the tendency, even in modern enlightened democracies, for politics to become more and more intellectually diminished.”

What are your experiences after almost three years as mayor in Wuppertal, especially in connection with the concept of future art that you developed, i.e. creative commerce interacting with economic, technological, institutional and cultural dynamics?

Schneidewind: “We might take the work of an artist like Tony Cragg as a starting point, whose installation of three stone columns entitled “Points of View” is also depicted on the cover of the book Die Große Transformation. What it comes down to is coaxing lightness out of a stubborn material, using the idea of what’s within the material of a block of stone and then the energy and perseverance needed to bring it out. An extremely motivating experience is that an urban area like Wuppertal is full of coartists, people sustained by the possibilities of making things more future-oriented, where they can join energies. And this is often what’s needed, because the political and administrative material is strong and it takes a lot of energy to make room for the delicate forms of the future. There are some wonderful successes, but also a lot of setbacks. Ideas get stuck in granite cores that are far too hard, and even when you keep chiseling away, you can’t get them to emerge cleanly. This tension is the key to shaping good urban policy.”

Henning Klüver conducted this interview with Uwe Schneidewind in May 2023.

(Translated from the German original)

Read other Articles from this Edition

Would you like to receive this Edition of our LAND Magazine?

All mandatory fields are marked with a *